Improving the Phase III WIP process and local government engagement

May 8, 2018

Mr. Benjamin Grumbles, Secretary

Maryland Department of the Environment

Montgomery Park Business Center

1800 Washington Blvd.

Baltimore, MD 21230

Re: Improving the Phase III WIP process and local government engagement

Dear Secretary Grumbles,

Thank you for the opportunity to provide input regarding the structure and content of local participation in Maryland’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan (WIP). A subset of Choose Clean Water Coalition members and other concerned partners appreciate the ongoing in-person and in-depth discussions with Maryland Department of the Environment, led by Lee Currey and your other colleagues on this topic. This letter follows those discussions. The undersigned members of the Choose Clean Water Coalition are pleased to present these detailed recommendations in pursuit of a successful process for Phase III WIP local engagement.

This letter, informed by significant outreach with advocates and local government representatives, is based on shared belief that in most cases local Phase II WIPs remain relevant and instructive. As such, we do not believe that the best value lies in asking local jurisdictions to “reinvent the wheel” by producing entirely new, separate Phase III WIP documents. Instead, we recommend that MDE, and its Cabinet member partners:

Develop numeric planning targets at the county level;

Assist local governments in undertaking an assessment that adapts their local Phase II WIPs to meet remaining challenges;

Strengthen incentives, permits and technical assistance to urgently and effectively address lagging stormwater and septic loads;

Outline an alternative implementation plan if local targets are not achieved;

Encourage cross-sector collaboration as much as possible, particularly between urban sources and agriculture; and

Fulfill EPA expectations to account for future growth and ensure robust BMP maintenance and verification.

Maryland took significant steps to plan for pollution reduction in the Phase II WIP, but Maryland is currently projected to fall short of reaching its 2025 goals. Moreover, we understand that wastewater treatment plants are no longer expected to close the remaining gap. This increases the urgency of accelerating progress in the non-point source pollution sectors: stormwater runoff, septic systems, and agriculture. Maryland can build on the progress made in the Phase II WIP and make changes in the Phase III WIP process in order to close the gap of pollution reduction by 2025. The Phase III WIP program evaluation and planning process provides counties with an opportunity to revise their WIPs to ensure they reach their pollution reduction targets by 2025. For counties that did not fully participate in the

Phase II WIP process, the midpoint assessment presents a fresh opportunity to join local and regional efforts to reduce pollution and to develop a viable plan for doing so.

In order for Maryland to achieve its 2025 goals, the state must establish a clear understanding of who is accountable for which targets and pounds of pollution reduction. We recommend an involved and collaborative approach with local governments, notably counties, to reach identified local targets and identified measures to hold every level of government accountable and provide reasonable assurance that targets will be achieved. The following provides specific points of analysis and recommendations.

SECTION 1. CONTEXT FOR RECOMMENDED ACTIONS

Maryland’s investment in the development of the Phase II WIP produced important results. WIP teams convened by state agency representatives and informed by key data enabled a diverse set of stakeholders to recommend WIP implementation measures that were relevant, applicable, and feasible at local and regional scales. County pollution reduction targets included during that process stimulated interest and creativity around proposed work and helped focus energy on discrete sets of programmatic and implementation actions. Although several recommended actions remain undelivered, they continue to have significant potential to underpin and motivate activity in the WIP’s third phase. There was also healthy diversity among participants, which should be maintained.

Recognizing the vital importance of local government investment in water quality improvement, NGO partners recently sought to better understand the value and results of various local accountability measures included in Phase II. In 2017, the Choose Clean Water Coalition held two round table meetings to review the performance of Phase II elements including county targets, milestone expectations, and progress reporting. Local government and NGO representatives in attendance heard updates relayed from MDE staff and discussed what the Phase III process should look like. Meeting participants laid out different options and assessed their pros and cons in making recommendations.

Through this process, we found that local governments were generally agreed that more direction from MDE would be helpful. While local governments are typically apprehensive to accept new regulatory proposals, many said that accountability played a key role in clarifying expectations, substantiating local investment, and generating interest from elected leaders. A number of local government representatives said that local targets are helpful and that continued support and direction from the state would be useful in Phase III.

SECTION 2. RECOMMENDED ACTIONS

SUMMARY

This letter will enumerate several recommendations for MDE to ensure the Phase III WIP process accomplishes the goal that EPA and Marylanders are counting on to close the gap between county level Phase II WIPs and our 2025 goals. Our engagement, dialogue, and experience partnering with local governments leads us to propose the following eight strategies as critical elements of a successful local engagement effort in the Phase III WIP planning process, and we encourage MDE to implement them:

I) County program assessment and Phase III gap strategy

Provide county governments with a template to complete a program assessment that identifies what has worked, what has not, and what is most needed to increase capacity for pollution reduction between now and 2025.

Based on this assessment, encourage county governments to update their local Phase II plans to provide a roadmap to reach 2025 goals.

II) County planning targets

Based on the state’s gap analysis and the local program assessment, collaboratively develop numeric county planning targets and clear lines of accountability and transparency for achieving them.

III) Enhanced milestone framework

Align state water quality funding sources to more fully support achievement of local milestones.

IV) Tools and technical assistance

Create ombudsmen positions and increase staff resources available to local governments to plan, prioritize, design, and secure funding for local milestone projects.

Refine optimization tools and develop a “lite” version of CAST to assist local scenario planning.

V) State implementation alternatives

Include in the Phase III WIP those regulatory, fiscal, or programmatic actions the state would need to take to make up for any implementation shortfalls associated with county planning targets.

VI) Alignment with permit requirements

Ensure consistency between restoration requirements in MS4 permits and county and statewide nutrient load reduction requirements in the Phase III WIP. See the Choose Clean Water Coalition letter sent to MDE on August 25, 2017 for more details.

VII) BMP Verification and Maintenance

Provide training to help counties participate in the state’s BMP verification protocols.

Establish an independent verification team to review BMP reporting and recommend improvements to tracking and maintenance protocols.

VIII) Accounting for Growth

In consultation with local governments, the development industry, environmental groups, and other stakeholders, adopt a robust Accounting for Growth policy that minimizes new or expanded pollutant discharges to the maximum feasible extent and fully offsets the remainder to ensure that it does not result in an overall net increase in pollution.

Process

Consider offering data resources and collaborative stakeholder opportunities like those undertaken by Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Target state resources to support partnerships and facilitate cross-sector discussion and implementation where appropriate.

Form a Local Working Group to advise MDE on local engagement in the Phase III WIP, including the program assessment, local gap strategies, resource needs, and the development of county planning targets.

DETAILED DISCUSSION

(I) COUNTY PROGRAM ASSESSMENT AND PHASE III GAP STRATEGY

Many of the undersigned organizations find that the Phase II WIPs provide valuable information about local conditions, local capacity to reduce pollution, and expected levels of BMP implementation over the Phase II planning period. Many local plans also identified specific opportunities to increase the rate of progress. Our experience working with local governments since that time has demonstrated that the local Phase II WIPs remain relevant and instructive. The central challenge in most jurisdictions at this time is not planning, but instead creating the conditions necessary to accomplish these plans.

As such, we do not believe that the best value lies in asking local jurisdictions to “reinvent the wheel” by producing entirely new, separate Phase III WIP documents. Instead, we recommend that MDE request counties to undertake a program assessment that builds on their local Phase II WIPs as the first step in local Phase III WIP planning. This assessment should lead to the development of a strategy to close any projected capacity or implementation gaps identified for the 2018-2025 timeframe.

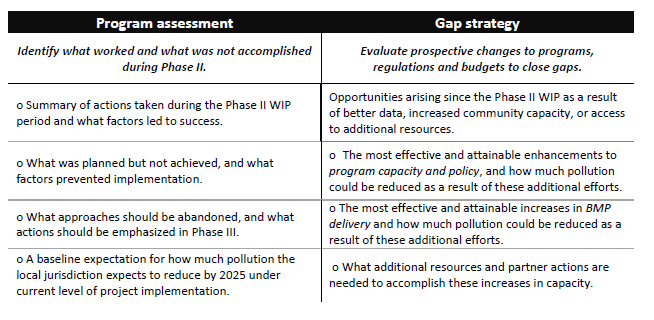

Specifically, the program assessment should identify what worked and what was not accomplished during the Phase II implementation period. The assessment should flag areas where the plan is off track, and evaluate prospective changes that can be made to programs, regulations, and budgets to accelerate progress related to programmatic capacity and BMP implementation. To have reasonable assurance that sufficient progress occurs going forward, MDE should encourage that the capacity enhancing measures included in the assessment are designed to achieve anticipated pollution reductions and clearly identify the resources needed for the enhancements to occur.

At the conclusion of this process, existing county WIPs should be updated to reflect the concrete strategies selected by the local jurisdiction to help close pollution reduction gaps identified in the Phase III WIP. MDE should provide a template for county governments to use in evaluating their programs and provide feedback to the Department. We recommend that the template include the following prompts and request feedback with any associated materials in writing:

The template should solicit descriptive information in objective and measurable terms wherever possible. Much of this evaluation could be facilitated and enhanced by integrating or cross-referencing other local planning documents, watershed restoration action strategies, and county budgets. For example, indicators of a county government’s capacity to implement projects could include an account of dedicated funding and staffing, program administration commitments, or local rules and regulations. Capacity can also be defined in terms of the factors that produce measurable progress toward milestone commitments or explicit support from county elected leadership. The gap strategy is an opportunity to highlight locally-dominant nutrient or sediment sources, as well as practices or procedures that have high potential to reduce pollution. To enable sufficient progress to be made going forward, planned actions must be specific about resource needs, increased budgets, and the methods intended to meet those needs.

While some sectors need substantial help, a focus on sector activity alone will not be sufficient. Maryland should encourage cost effectiveness to get the most pounds of pollution reduction for every dollar spent while also ensuring equity in responsibility and shared benefits. It is critical that MDE increase its local engagement around the Phase III process to ensure localities understand how important their role is in identifying opportunities to reduce costs and accelerate project delivery in pursuit of 2025 goals. As such, the local program assessment should also prompt conversations with other sectors participating in the Phase III WIP. Specifically, the template should prompt discussion and report on:

Coordination between county government and agricultural representatives to identify collaborative projects or cost-sharing/savings strategies;

Coordination between county government and municipalities to evaluate potential partnership on stormwater projects, sewer infrastructure, and other BMPs;

Expected capacity of local and regional non-governmental institutions and organizations to implement BMPs within the jurisdiction; and

A preferred structure for ongoing communication between sectors and stakeholders during WIP implementation.

Proposed schedule:

We recommend that MDE provide local jurisdictions with guidance for conducting a program assessment by the middle of June 2018 and request responses by the middle of August 2018. This would provide MDE with valuable information to help finalize local area planning targets, as discussed below. Furthermore:

Regional WIP meetings (scheduled for May-June 2018): survey and brainstorm to refine program assessment template;

County program assessments (June-August): counties complete template, which includes the program assessment and a preliminary gap strategy;

Regional WIP meetings (we propose September 2018): synthesize results & reflect to stakeholders;

County targets (November 2018): MDE provides county targets as discussed below; and

County gap strategies (February 2019): counties finalize gap strategies based on local planning targets for inclusion in the draft Phase III WIP. This step should include a specific opportunity for public input prior to submitting the final strategy.

(II) NUMERIC COUNTY PLANNING TARGETS

The Phase III WIP should include numeric county planning targets that clearly define the pollution reduction responsibility attributed to each sector, including agriculture. County targets should be developed through a collaborative process and be provided jointly to the county governing body and the local Soil Conservation District to leverage the strengths of these institutions and maximize effectiveness and collaboration. Through the program assessment phase, counties provide key background information and local context that supports the development of planning targets and establishes critical interest in actions that result in targets being achieved.

We expect that county targets will not require that local jurisdictions close the entire remaining statewide gap on their own, but should, together with measures by the state and other permit holders and soil conservation districts, represent a fair-share effort towards achieving the total caps. This must be connected to, but go beyond, stormwater practices in MS4 counties.

Focusing the Chesapeake Bay partnership’s effort at a small scale was identified as one of the biggest capacity needs during the Phase II WIP. EPA’s interim expectations for the development of Phase III clarify that the Phase III WIP should include measurable planning goals below the major-basin scale.

Local area planning targets at the county scale are therefore critical to the success of Phase III and are necessary to demonstrate reasonable assurance that the Chesapeake Bay TMDL will be achieved. It is imperative that numeric pollution reduction goals match the scale of decision-making authority and existing structures for project delivery that reside with local governments. In Maryland, most stormwater facilities, septic systems, and small wastewater treatment plants are managed by county and municipal authorities. Implementation of agricultural BMPs is coordinated by local Soil Conservation Districts. While some cooperative regional structures exist, most are largely unequipped and in many cases lack experience to implement a comprehensive watershed restoration program.

Many local government partners report that concern with local targets in the Phase II WIP was rooted in the inability of the Chesapeake Bay Model to provide reliable estimates and projections at a detailed geography at that time. The current model contains greatly improved land use information that has been reviewed and endorsed by the Bay Program partners.

In addition, some counties felt that Maryland’s process for allocating loads advanced without proportionality between the responsibility to reduce loads and the available capacity and most cost-effective opportunities to do so. Since then, the Chesapeake Bay Program partnership has improved the capabilities of the Model and convened a Task Force that has recommended viable methods for arriving at local planning targets. In December of 2016, the Task Force informally called for local goals to be U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Interim Expectations for the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (Interim Version – January 19, 2017) established in partnership with local and regional partners, stakeholders, and federal and state facilities going forward, at a scale below the state-major river basin.

For Phase III, we recommend that MDE provide counties with numeric local area planning targets that represent attainable but accelerated goals for enhancing program capacity and implementation. The goals should be defined in terms of actions that provide MDE reasonable assurance pollution load allocations will be met overall. A county goal can facilitate an increase in coordinated action across sectors and across county lines, and prompt a focused effort on priority action while ensuring that reported progress is accounted for and validated to reach the total 2025 goal.

Under the current allocation framework, requiring local jurisdictions to close the entire remaining gap for non-point sources is expected to be very difficult. In general terms, Maryland’s Phase III WIP strategy should be the sum of reductions already achieved, reductions expected under current programs, and a combination of enhanced state and local strategies to close the remaining gap.

This means that, rather than setting an expectation that the county planning target requires local jurisdictions to close the entire remaining gap for non-point sources, county targets should instead represent a well-defined expectation for a substantial increase in local capacity to deliver BMPs. In other words, for sectors that are off track at the midpoint assessment, we would expect the local target to reflect an increase in the pace of implementation that is greater than current level of effort but less than the total sector burden. This, in combination with state stormwater and septic strategies, plus other sector allocations, should result in a plan to close the remaining gap.

The magnitude and fitness of a goal at the local level could be based on:

The gap remaining after expected or proposed statewide strategies are applied;

Work by the Chesapeake Bay Program to identify the “reducible” load within a county;

Information that identifies the locally dominant nutrient or sediment sources;

Information on the cost and benefits of BMPs suited to a particular jurisdiction;

The program assessment that examines local progress, capacity, and feasibility of implementation actions; and

Opportunities for collaboration with municipal governments, soil conservation districts and NGO partners.

There are differences of opinion over exactly how sector boundaries should be defined and if and to what extent they should be used within the local planning target framework. Several rural jurisdiction representatives felt they had no control or exact data on the largest pollution sources in their county -- namely agriculture. We understand the potential for cost savings and faster implementation that comes with such flexibility; however, a single planning target that is everybody’s responsibility could quickly become nobody’s responsibility without shared accountability measures in place. If provided by sector, the magnitude of these targets could still be balanced among counties across the state to focus the majority of a specific county’s effort on the most pressing and potentially cost-effective solutions within that jurisdiction.3 Knowing and evaluating progress across sectors and better understanding who is responsible for each piece of a pollution reduction plan will be very useful. In no case should local targets reduce or rescind a load reduction required in an existing permit. Regardless, Maryland needs to ensure there are clear lines of accountability for who is ultimately responsible for pollution reduction.

(III) ENHANCED MILESTONE FRAMEWORK

Feedback from local staff and elected officials at the roundtables last fall highlighted the value of local milestones in maintaining focus and effort towards pollution reduction goals. In short, county milestones for planning and implementation provide focus and coordination for restoration activity at the local level.

We believe that MDE should continue this accountability structure in Phase III and better coordinate the deployment of financial resources and technical assistance with achievement of local milestones. Doing so would increase the incentives that encourage localities to actively participate in the Phase III WIP process. Maryland should invest more funds in county resources, particularly to encourage and reward attaining milestones.

As a first step, we recommend that MDE and DNR increase the proportion of state funding that flows through the Local Milestone Implementation Grant program. We also recommend that these agencies adjust the scoring systems of the Bay Restoration Fund and the Trust Fund to support projects proposed by local jurisdictions that are actively pursuing local milestone commitments. Specifically, MDE should consider refining its Integrated Project Priority System in order to steer funding toward these jurisdictions and projects.

Moving forward, the state should allocate more funding to MDE and relevant agencies to properly administer this enhanced milestone framework. For example, Maryland’s capital budget for water programs has been reduced to well below the historic average in recent years. It would be counterproductive to continue these deficient levels of capital support given the tremendous need for restoring our water infrastructure systems and accelerating progress to meet our 2025 TMDL targets. Instead, we recommend that MDE propose to increase capital spending for pollution reduction programs administered by the Water Quality Financing Administration. Additionally, we hope DNR and the Bay Cabinet will consider engaging in discussions on how to set aside or increase similar incentive funds from the Chesapeake and Atlantic Coastal Bays 2010 Trust Fund to reward strong local performance. MDE will have to balance the use of incentives with the need to place investments where they can be done in the most cost-effective way.

(IV) TOOLS AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE

Local jurisdictions will require additional resources in order to meet the goals as defined in this phase of the Bay TMDL. MDE can play a valuable role in supplying tools and technical assistance that better prepare localities to accomplish what the state asks of them.

Based on our understanding of local needs, we suggest that MDE place a priority on refining tools for local scenario planning and optimization. Specifically, MDE could:

Update and promote Center for Watershed Protection’s optimization tool

Develop a “lite” version of CAST and provide training to county staff and/or retain MDE staff or consultants to help run scenarios at county request

Another investment that MDE should consider is the placement of ombudsmen with local jurisdictions to assist those areas with planning and implementation of BMPs for the purpose of WIP implementation. Ombudsmen may assist with identifying, prioritizing, permitting, and securing funding for projects. This may also offer an alternate way to address when jurisdictions fail to reach acreage requirements in nonpoint source MS4 permits.

With a full cycle of MS4 permits to evaluate, it has become clear that adequate investment in the supporting tasks of project identification, prioritization and permitting is a key driver of progress. For example, Anne Arundel invested in stream assessments for the 10 years prior to the latest MS4 permit and as such, has a backlog and priority of projects. It has streamlined its permitting process and while not perfect, it is moving forward and making progress. In contrast, in some other urban jurisdictions there is no backlog because the projects that have been identified have not been prioritized and the permit process is still overly cumbersome.

On the Eastern Shore, MDE is partnering with an NGO and local jurisdictions to leverage funds from EPA that are enabling investment in a technical service provider that is shared by multiple localities. The pilot project will help unregulated and Phase II MS4 jurisdictions in this region maximize limited resources with a goal of planning, prioritizing, and streamlining delivery of projects for WIP credit. Models similar to this could be replicated in other rural regions of Maryland where under-resourced localities that are not subject to a stormwater permit face significant capacity constraints. The location of an ombudsman position like the one being piloted on the Shore could be determined in part by the degree to which presiding jurisdictions are investing in closing the gap to meet their 2025 goals.

Maryland is fortunate to have several technical service delivery structures already in place that could be refined or enhanced to support a statewide local ombudsmen program. MDE could reinvest in staff resources directly to support this work. The Watershed Assistance Collaborative and the University of Maryland Sea Grant Extension supply restoration specialists to support local projects and priorities. MDA’s Soil Conservation Districts and Resource Conservation and Development offices both contain seasoned and skilled stormwater management practitioners. Regional Councils offer key services to multiple counties with similar needs. These entities, with modest additional investment or reprioritization, could be leveraged to increase staff capacity to support WIP obligations.

Staffing vacancies at MDE should also be filled and assigned to support local jurisdictions with their water quality improvement efforts. Funding for technical assistance could come from a variety of sources. State agencies could apply as-yet unused legislative appropriations for staffing. The Trust Fund could provide measured outlays for technical assistance. An ombudsmen program may also be funded by leveraging resources from multiple partners who share in the cost of the program’s delivery. The Eastern Shore pilot offers an attractive model where partnering local jurisdictions, MDE, and EPA through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation share in the cost of the ombudsman position that serves six localities. Other funding partners could include the Rural Maryland Prosperity Investment Fund, which has been receiving a growing allocation from the Maryland General Assembly and could be tapped to further diversify and minimize financial commitments from any single entity.

The ombudsman and other forms of technical assistance should help not only accelerate progress towards nutrient reduction and optimization of cost effective measures, but also ensure projects and BMPs create multiple benefits through Green Infrastructure (GI) and other innovative strategies. State and local Phase III WIP planning should project how proposed project will reduce other pollutants of local and regional concern, and preference should be given to strategies that address multiple pollutants. In many cases, projects and activities can be chosen to reduce nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment while also removing other pollutants. For example, EPA studies on Green Infrastructure bioretention systems show that they can also effectively remove significant heavy metals.4 Green Infrastructure projects tend to remove or treat other pollutants and provide multiple benefits while helping to meet nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment goals. Riparian buffers, for example, can also provide several benefits. While the three main pollutants should remain the main focus of the Phase III WIPs, MDE should explore ways to encourage other non-nutrient TMDLs into the Phase III WIPs. We also approve of MDE’s incorporation of salt and deicing in the new MS4 draft templates.

(V) IMPLEMENTATION ALTERNATIVES

Our organizations believe that the Phase III WIP will best be positioned for success when state and local reduction commitments, policies, and investments are coordinated and working together. However, we are cognizant that a variety of factors could result in counties, soil conservation districts, and permitted entities falling behind local pollution reduction targets. In this regard, it is imperative that MDE outline in the Phase III WIP the specific actions that it will need to take to maintain a suitable 2025 trajectory if regulatory or programmatic changes are not made as expected in local permits and Phase III WIP gap strategies. This “second pathway” or “contingency plan” to achieving the 2025 goals could help Maryland’s Phase III WIP meet the reasonable assurance standard in the Clean Water Act and clarify expectations and alternatives for all stakeholders. This contingency plan should be included as a section in the Phase III WIP.

For permitted entities, corrective actions should accelerate pollution reduction work that is in non-compliance or behind schedule to maintain the pollution reduction timetables outlined in the WIP. Corrective actions in noncompliant jurisdictions may include increasing pollution reduction activity or responsibility, hiring of additional staff or ombudsman to perform technical assistance and add capacity, or withholding of other funding. Any deadline extensions should not push back work anticipated by the WIP under a future permit; instead, these responsibilities must be cumulative and be satisfied concurrently. MDE should also promote public transparency in their compliance programs, in line with the practices of many neighboring states.

For unregulated sectors and jurisdictions, MDE should outline those state policies that would be needed to fill any gaps in achievement of local targets. For example, the state may find it necessary to require Best Available Technology on new or replacement septic systems beyond the Critical Area in jurisdictions that are unable to make progress in that sector through other means. Or as a fiscal example, the state may need to reallocate local distributions of the Bay Restoration Fund to tackle the most significant local sources of pollution.

For both regulated and non-regulated entities, MDE and MDA should consider use of a third party to assess the activity in a jurisdiction that is determined to be off track with pollution reduction targets. This third party could provide independent recommendations for increasing capacity or efficiency that could help improve the rate at which projects are implemented during the permit lifecycle or other relevant schedule. The third party could be sourced from EPA, the Chesapeake Bay Program, or an authorized technical service provider.

(VI) ALIGNMENT WITH MS4 PERMIT REQUIREMENTS

Improvements in water quality are directly tied to the amount of pollution from upland sources that surface waters receive. In the wastewater sector, EPA and MDE regulate point source dischargers based on levels of nitrogen and phosphorus leaving the permitted facility. This regulatory structure has proven effective at ensuring damaging pollutants are adequately controlled. Permitted dischargers of stormwater should similarly be required to treat polluted runoff on a direct water quality basis rather than solely on a water quantity basis.

The MS4 permit program must continue providing a strong regulatory framework for all jurisdictions to meet Clean Water Act requirements. Recent conversations with MDE have suggested that the agency may make multiple changes to the program that, in our view, would represent backsliding compared to current requirements, including expectations outlined in the Phase II WIP. Ongoing enforcement and technical assistance from MDE are both necessary to ensure MS4 jurisdictions continue working to address their stormwater challenges. Lack of funding, permitting timelines, budgetary cuts, or waiting for nutrient trading markets are not acceptable excuses for missing MS4 permit deadlines.

Phase III WIP restoration methodology and metrics should directly connect MS4 permits to the amount of pollution a water body can safely assimilate based on the applicable TMDL. For the next generation of Phase I MS4 permits, Waste Load Allocation (WLA) reduction requirements should be combined with durable Green Infrastructure restoration requirements to meet the Chesapeake Bay TMDL, local TMDLs, and stormwater volumetric reductions. The inclusion of a requirement to meet WLAs with a minimum GI requirement will support both water quality improvements and runoff reduction for local waterways and the Chesapeake Bay.

Establishing the WLA as the ultimate reduction target sets a clear and transparent standard for pollution reduction. By establishing GI targets in permits, regulated dischargers would be compelled to implement the most efficient and cost-effective pollution control technology available, providing confidence that projects on the ground will achieve water quality targets. Under this methodology, the GI requirement in a permit would not be a percentage of the county’s impervious surfaces (e.g. 20%) expressed in acreage but rather a percentage of the WLA (e.g. 40%) expressed in pollutant pounds that come from projects and practices with efficiencies approved for credit by the Chesapeake Bay Program. A GI standard tied to water quality in permits would enable MDE to demonstrate greater assurance to EPA that stormwater pollution reduction targets are being met. Moreover, while green infrastructure and many stormwater BMPs are often deemed as not “cost-effective” they are, in fact, economically efficient options given the plethora of health, environmental, climate, and economic benefits. MDE should help local governments use the Bay Program’s new “optimization engine” and tools as a way to prioritize such multi-benefit BMPs. Additional details on our recommendations for MS4 permits are included in the Choose Clean Water Coalition letter sent to MDE on August 25, 2017.

(VII) BMP VERIFICATION AND MAINTENANCE

The importance of strengthening verification protocols in Maryland at this point in time cannot be overstated. In order to meet Bay TMDL goals, MDE and local jurisdictions need to accelerate the pace of projects, as well as provide proper verification that leads to well-maintained BMPs throughout their life cycle. As stated by the Validation Panel of the Chesapeake Bay Program, assuring transparent and accurate BMP meets definition verification was, and remains, critical to achieving true long-term improvements in water quality and establishing public trust.

Verification and validation are of utmost importance. Especially since non-validated BMPs and programs will no longer get any credit under the new Bay model, outreach to localities to ensure they have proper monitoring, evaluation, maintenance and compliance assurance procedures in place is paramount. Otherwise, localities may be surprised and discouraged by progress that is less than expected towards the 2025 cleanup goals.

According to surveys of six counties in 2015, only 42% of BMPs were in good condition. Another 25% are failing in ways that negate most aquatic resource protection benefits and the remaining 33% are in need of maintenance.5 When BMPs are not maintained properly, they are not effectively performing the pollution reduction that was designed and counted. Maintaining existing BMPs is one of the most cost effective methods of maximizing the results of local efforts to reduce pollution. Supporting agencies in improving compliance is usually the quickest, least costly, way of dramatically improving water quality.

Maryland would benefit from an independent verification team and more funding to execute the protocols. To improve practices, verification needs to be carried out in conjunction with on-the-ground assessment and technical assistance as much as possible, especially in non-regulated sectors such as agriculture, stormwater facilities in rural jurisdictions and forestry.

MDE and other agencies in Maryland need greater capacity to ensure the verification plan is fully executed. We commend MDA for proposing to establish a BMP Verification task force, but we have not received further information on the establishment of the group or its work. If this proposal has been carried forth, the state should consider expanding the task force to supplement verification activities across BMP sectors, not just agriculture. Additional funds should be allocated to MDE, DNR and MDA in order to spearhead this verification task force.

(VIII) ACCOUNTING FOR GROWTH

The Phase III WIP process must incorporate the means to account for any increases in pollution loads created by growth in the urban stormwater, wastewater, and agricultural sectors. For example, Maryland is losing nearly 2,000 acres of forest land per year to development. According to Chesapeake Bay Program loading rates, this conversion can result in a four-fold or more increase in pollution on a per-acre basis.

EPA is placing a priority on growth offsets in the Phase III WIP. In its January 2017 Interim Expectations, EPA states:

Gaps in programmatic capacity the jurisdictions will need to address in the 2018-2025 timeframe through their Phase III WIPs include...Building the programmatic infrastructure, tracking systems, policies, legislation, and regulations necessary for fully accounting for growth, and offsetting all resultant new or increased pollutant loads through 2025. (p 2)

MDE should make certain that counties have the information needed to plan in ways that do not jeopardize or counteract the pollution reduction progress they are making. The Phase III WIP must include a viable policy that quantifies the amount of new pollution created from growth and ensure that these loads are fully offset. Specifically, the policy must ensure that any activity within its jurisdiction that will produce a new or expanded discharge of nitrogen, phosphorus, or sediment will be reduced or met by offsets. The discharger of the increased pollutant must be required to mitigate the increase at the source or secure one or more legally enforceable offsets before that activity may commence. This is required under the Clean Water Act and EPA’s implementing regulations.

SECTION 3. COLLABORATION DURING PHASE III WIP DEVELOPMENT

There is no need to start from scratch in the Phase III WIP. But this does not mean MDE should refrain from actively engaging and supporting local government action between now and 2025. The momentum and water quality improvements accomplished through local participation in Phase II need continued structure, support, and accountability. We urge MDE and the full Bay Cabinet to move forward rather than step back from its leadership role in fostering a coordinated state and local response to the water quality challenges facing the Bay and local waters.

MDE should prioritize stakeholder support in the process and give direction to all of the parties that will be executing WIP plans. There has been significant turnover of staff and leadership in some local jurisdictions. This often means that, even in jurisdictions with a strong Phase II WIP, local elected officials and staff would benefit from outside knowledge and expertise to properly structure and execute a gap strategy as part of the phase III WIP. Our experience is that many local governments welcome more guidance and education. Pennsylvania has had informational and financing workgroups meet on a biweekly basis since the fall. Pennsylvania also has created a toolbox that includes GIS modeling and monitoring data. Maryland might explore using these workgroups and tools as a model.

14

Virginia is also engaging Planning Districts and Soil Conservation Districts in regional engagement and collaboration.

Partnerships

The Phase III WIP is a prime opportunity to focus support on partnerships that can get more done faster and for less money. While capacity assessments and pollution reduction goals can prepare local government partners to increase the performance of actions taken in Phase III, non-government organization (NGO) and public and private technical service providers can provide additional capacity to close remaining pollution reduction gaps.

The undersigned organizations and our partners work diligently with local governments to provide value in accelerating the progress of pollution reduction as well as educating elected officials, policymakers, and the public in localities. There is great interest in engaging nonprofit organizations to help educate the public and policymakers about the importance of pollution reduction policies. In addition, many Foundations are actively providing financial support for local government outreach, financing options, and other implementation tools. Because much of the low hanging fruit has been picked, nonprofits and businesses can be helpful in continuing to accelerate the progress of projects. However, to be more effective, we recommend that the state target more funding and resources to encourage these public-private partnerships.

There are also several opportunities for collaboration between agriculture and urban/wastewater sectors. More exchange of information such as progress reports and collaboration between Soil Conservation Districts and local government could produce cost-effective opportunities for pollution reduction. This is especially the case in non-regulated or newly-regulated jurisdictions. A diversity of agencies and sectors can also bring different elements to the table that make partnerships powerful synergistic forces. For example, SCDs bring experience and expertise in the design and delivery of projects. Local governments have an administrative structure, public land, and a method for engaging private property owners in placing BMPs on their land. Discussions facilitated by the program assessment and ombudsman role outlined earlier in this letter could aid in facilitating these local partnerships.

Local Working Group

MDE should initiate regular meetings with local governments and other stakeholders to communicate expectations and solicit feedback associated with the Phase III WIP as soon as possible. Local elected officials in particular need ongoing education on this process. In addition to outreach, we recommend creating a standing working group for local engagement in Phase III WIPs. The working group would advise on matters related to local engagement and provide an open forum in which to develop county planning targets. This body could also inform other outstanding issues related to the Phase III WIP, such as sector allocations. At a minimum, workgroup membership should include representatives from:

Urban and rural, county and municipal stakeholders, including elected leaders and staff

Soil Conservation Districts

Bay Cabinet agencies

Agricultural sector

Private-sector water quality restoration professionals and businesses

Chesapeake Bay Commission

The NGO community

SECTION 4. CONCLUSION

The final push to 2025 has begun and Maryland must apply every effort to accelerate progress toward that goal line. In order to reach it, MDE will have to do more to assist localities, magnify engagement, create incentives for exceptional performance, provide more resources, and maintain effective transparency and accountability—including enforcing corrective actions when needed. The recommendations above are intended to provide a framework for local engagement that can be leveraged to address other issues that EPA and Bay Program partners expect to tackle in the Phase III WIP. For example, we understand that MDE plans to take climate change into account as the letter sent last year from the Choose Clean Water Coalition recommends. We urge MDE to help engage localities to ensure they know how climate change will affect them and how it should be incorporated into their planning and Phase III WIPs.

In closing, we view the challenges ahead as MDE’s best opportunity to reaffirm and invest in a holistic and comprehensive water quality restoration approach that ensures more nonpoint source pollution projects go into the ground faster and remain well maintained. Reaching the Chesapeake Bay TMDL 2025 goals will require a Phase III WIP process that allows all partners to share clear expectations and accountability for progress along with the tools and support needed to get the job done.

If you have any questions, please contact Ben Alexandro, Maryland League of Conservation Voters, at balexandro@mdlcv.org and Erik Fisher, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, at EFisher@cbf.org.

Sincerely,

1000 Friends of Maryland

Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

Anacostia Watershed Society

Annapolis Green

Audubon Maryland-DC

Audubon Naturalist Society

Back Creek Conservancy

Back River Restoration Committee

Baltimore Tree Trust

Blue Water Baltimore

Center for Progressive Reform

Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Clean Bread and Cheese Creek

Clean Water Action

Conservation Montgomery

Corsica River Conservancy

Dorchester Citizens for Planned Growth

Ducks Unlimited

Earth Forum of Howard County

EcoLatinos

Friends of Sligo Creek

16

Friends of the Bohemia, Inc

Friends of the Nanticoke River

Little Falls Watershed Alliance

Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association

Maritimas

Maryland Conservation Council

Maryland Environmental Health Network

Maryland League of Conservation Voters

Mattawoman Watershed Society

Montgomery Countryside Alliance

Nature Abounds

Natural Resource Defense Council

Neighbors of Northwest Branch

Oyster Recovery Partnership

Potomac Conservancy

Queen Anne's Conservation Association

Rachel Carson Council

Rock Creek Conservancy

Savage River Watershed Association

Severn River Association

Severn Riverkeeper

Shore Rivers

Sierra Club- Maryland Chapter

Southern Maryland Audubon Society

South River Federation

Sparks Glencoe Community Planning Council

St. Mary's River Watershed Association

Talbot Preservation Alliance

Waterkeepers Chesapeake

West & Rhode Riverkeeper

Wicomico Environmental Trust

cc:

D. Lee Currey, MDE State of Maryland Bay Cabinet

EPA Region 3 Chesapeake Bay Program partners Maryland Department of Agriculture Maryland Department of Planning Maryland Department of Natural Resources Maryland Association of Counties Maryland Municipal League